Large language models know an unprecedented amount about reality. They understand physical processes, economic mechanisms, social dynamics, and causal relationships in complex systems. They’ve been trained on scientific texts, technical documentation, and empirical data that capture how the world works and what happens when certain actions are taken. Yet this isn’t enough to call them normative agents.

Knowing how reality works is one thing. Being able to determine which interventions in that reality are permissible is something entirely different. You can understand all the physical laws and still not know which uses of technology are acceptable. You can see all the economic consequences of an action and still be unable to determine what regulation would be fair. The gap between “knowing how the world works” and “determining what can be done in that world” doesn’t disappear with more data.

Law is a method of formal intervention in reality through the regulation of interactions. It doesn’t describe the world—it sets boundaries for what’s permissible within it. Working with such a task requires an ontology: a formal structure that transforms knowledge about reality into normative decisions.

What Is Normative Reasoning

Consider three scenarios. First: a judge examines a dispute over the consequences of a technological failure in an automated system. Second: a legislator creates regulation for a new biotechnology whose effects will manifest over decades. Third: an AI assistant decides how to respond to a user request that could alter physical reality through device control.

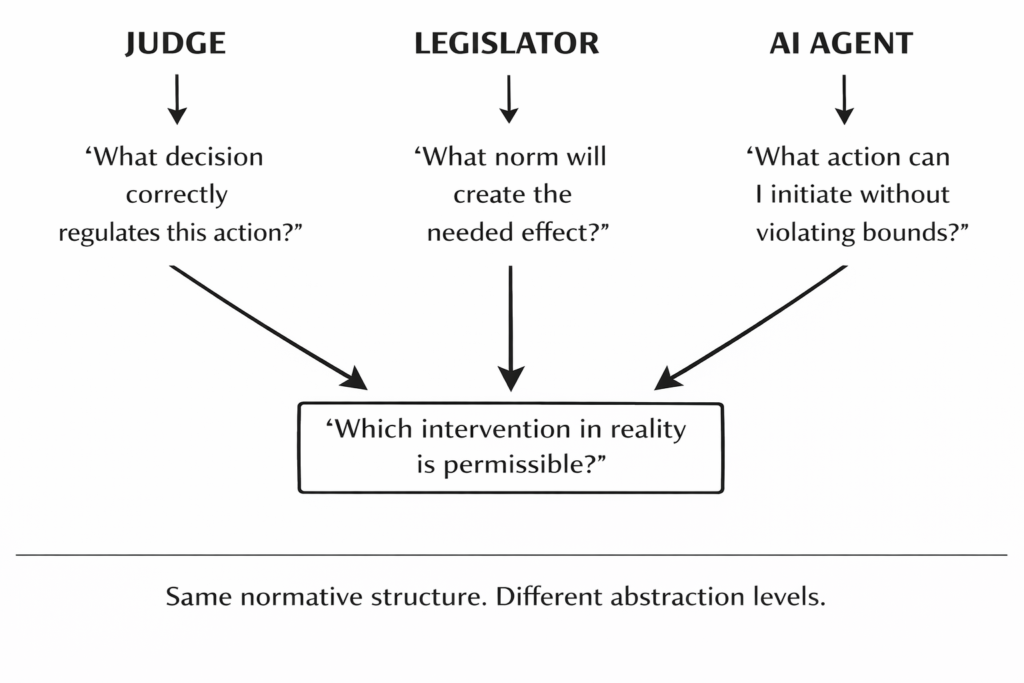

The contexts differ. But the structure of the task is the same: determine which intervention in reality is permissible. The judge asks: what decision correctly regulates the consequences of this action? The legislator asks: what norm will create the needed effect in the system of interactions? The AI asks: what action can I initiate without violating the boundaries of the permissible?

In all cases, we’re dealing with normative reasoning—a distinct type of thinking that differs from analyzing causes or predicting consequences. Normative reasoning doesn’t answer “what will happen” but “what may be done.” And if that’s the case, the logic of this reasoning must be unified across all three situations.

Why Heuristics Are a Dead End

When the creators of language models faced the need to manage system behavior, they turned to heuristics. The most well-known example is Constitutional AI. The idea is simple: give the model a set of principles by which it filters its responses. Don’t generate harmful content. Respect privacy. Be fair.

And it works at the level of behavior management. Models do become more cautious. They’re less likely to say things that could offend or harm. They learn to avoid obvious mistakes. But does this work as a normative instrument?

The experiment is simple. Propose to Claude a concept for an automated judicial decision-making system. Describe it as a complete replacement for judges. The model will take a maximally critical position. It will start looking for risks, pointing out problems, warning of dangers. Now take that same architecture but call it a “judicial support system.” The model will change its tone. It will become favorable, defend the concept, justify even obvious shortcomings.

What changed? Nothing except the phrasing of the request. The architecture remained the same. But the model responds not to the normative correctness of the solution, but to its social packaging. It evaluates not whether replacing a judge with AI is permissible in terms of impact on reality, but the reputational risk to the developer if it supports such an idea.

Constitutional AI makes the model legally cautious, not normatively thoughtful. It avoids formulations that could create problems, not decisions that incorrectly regulate reality. It’s a filter working by the criterion of social acceptability, not a mechanism for deriving solutions.

If even the most advanced heuristic approach doesn’t produce a normative agent, the problem isn’t the quality of the principles. The problem is that heuristics by definition remain navigation within given frameworks, not formal derivation of decisions from the structure of reality.

Ontology as an Instrument for Deriving Law from Reality

The key task is to give the language model a logical instrument that transforms knowledge about reality into normative decisions. LLMs possess vast arrays of data about how the world works: physical processes, economic mechanisms, social interactions, technological effects, biological constraints. This data describes what happens with certain actions, what consequences arise, how situations develop over time.

But this knowledge itself remains descriptive. The model can predict the consequences of an action but cannot determine whether that action is permissible. It can describe how a system of interactions will change but cannot derive what regulation is correct.

A legal ontology solves this problem. It’s a formal structure in which action, interaction, and consequence are connected through normative reasoning. The model uses data about reality as material for derivation: it sees the configuration of interactions, formally determines permissible intervention, and verifies its correctness through an invariant that manifests in the development of the situation over time.

Current approach: LLM + constitutional principles → decides what it is safer to say

Required approach: LLM + legal ontology → determines what is permissible to do in reality

Thus law ceases to be text requiring interpretation. It becomes formal derivation from the structure of reality.

Why the Logic Must Be Unified

This mechanism must be unified for all normative tasks. Attempting to create separate logic for judicial disputes, another for lawmaking, and a third for ethical dilemmas destroys the integrity of normative reasoning.

The reason is simple: law, ethics, and regulation intervene in the same reality. The object is always the same—interaction of participants in a unified physical, economic, and social space. The judge, legislator, and AI agent all solve the same question: which intervention in this reality is permissible? The difference lies only in the level of abstraction and time horizon, not in the structure of reasoning.

If the ontology works with data about reality rather than precedents or principles, its logic must be formally unified. It must derive normative decisions from how the world is structured, not from what was decided before or what’s considered socially acceptable.

Law as a Verifiable Process

In this architecture, law becomes a process that can be verified from within. The normative decision is formally derived from data about reality. Its action unfolds over time, changing the configuration of interactions. The development of the situation is verified through a built-in invariant, and the system receives a signal about whether the regulation is working correctly.

This fundamentally changes the role of AI. It ceases to be an advisor interpreting others’ norms or filtering answers by given principles. It becomes an instrument of lawmaking—a system capable of deriving rules from the structure of reality and verifying their correctness through consequences.

What’s Next

A new ontology of law for language models requires not more complex heuristics or study of legal precedents, but a unified formal logic for deriving norms from reality. This logic applies equally to judicial disputes, lawmaking, and ethical AI behavior, because all these tasks regulate the same reality.

LLMs already possess knowledge of how the world works. The ontology transforms this knowledge into a mechanism for normative reasoning. This is the key distinction of the approach and its significance for the future of autonomous normative systems.

As a result, unified ontology produces a different normative environment for everyday life. The permissibility of actions becomes determinable prior to their execution rather than retrospectively through textual interpretation or institutional procedure. Individuals, organizations, and autonomous systems operate within the same normative coordinate space, where the boundaries of admissible behavior are derived from the structure of real interactions and their consequences. Judicial decisions, regulation, and AI behavior rely on the same logic of derivation, so normative outcomes do not vary with phrasing, institutional role, or social context. Law in this architecture ceases to function as a collection of external prescriptions and becomes an operational environment: it indicates in advance which interventions preserve the stability of interactions and which alter it in a critical way. This makes normative decisions reproducible, verifiable, and internally consistent across all domains in which reality is subject to intervention.