Over the past year, I’ve worked closely with numerous family law practices as design partners, helping them understand where time really goes and why certain inefficiencies persist even in well-run practices. One recurring theme continues to shape how I think about this work.

Attorneys walk me through their document management systems, which are often sophisticated, well-organized, with smart search and automatic classification. The systems reflect best practices: clean folder structures, thoughtful naming conventions, OCR on everything, and automatic routing of intake documents.

Then I ask them to walk me through preparing for a settlement conference scheduled for the next day.

Most attorneys commence this process by opening the relevant client file and begin what’s termed creating the “complete picture” or “whole story”. As an example, one attorney pulled up financial documents to verify the current asset situation, cross-referencing bank statements across multiple accounts. Checked notes from her client meeting regarding offshore accounts. Checked tax returns against stated income on disclosure forms. She reviewed email chains to confirm what the client had said about equity compensation. Remembered taking notes during a meeting about the developments following the email correspondence, and checked her notes again. She scanned through the client and their partner’s communication history to reconstruct the timeline of custody discussions. She verified dates on property documents against the marriage date.

On average, four hours later, she would have what she needed: a comprehensive understanding of her client’s situation that would allow her to negotiate effectively.

“I do this before every major event in a case,” she explained. “Settlement conferences, court hearings, significant client meetings. I need to be prepared for one of the most important days in my client’s life, and for this, I must have the complete picture in my head.”

Her document management system was excellent, and she was even more organized than most. But organized information isn’t the same as integrated understanding of a client’s complete situation.

The Work We Don’t See, Which Dominates Practice

Family law attorneys spend enormous amounts of time on work that’s largely invisible, but incredibly important: mentally assembling information into comprehensive understanding.

You have all the pieces. Documents are properly organized and easily accessible. Financial information is filed correctly. Communications are searchable. Everything is there, but before you can do meaningful strategic work, before you can negotiate effectively, draft persuasively, or advise confidently, you need to build a mental model of the client’s complete situation. Building that model requires gathering information from multiple sources and integrating it into coherent understanding.

This reconstruction work happens constantly throughout a case.

Before client calls, you refresh your memory about where things stand. Before drafting motions, you verify facts across multiple documents. Before settlement discussions, you reconstruct the complete financial picture. Before custody hearings, you review all relevant communications and circumstances.

Each time you return to a case after working on other matters, you’re revisiting and, to an extent, also rebuilding your understanding. The important documents may not have changed, but your mental model has faded. This work is cognitively demanding because you’re not simply reading, you’re integrating information, cross-referencing facts, verifying consistency, identifying what’s current, and building connections between pieces that exist in different places.

The time investment is substantial: hours before major events, thirty minutes before client calls, fifteen minutes before responding to opposing counsel. The cumulative impact on practice capacity is far larger than most attorneys realize.

Why This Problem is Particularly Acute for Family Law Practices

Other practice areas don’t encounter this problem to the same degree.

For family law attorneys, client circumstances evolve constantly throughout representation. Income changes, living situations shift, new relationships form, children’s needs evolve, and the list goes on. Each change means your previous understanding is partially outdated, requiring reconstruction that incorporates new information while maintaining relevant context.

To make this more complicated, information arrives continuously and in fragmented form. Clients send documents gradually as they locate or receive them, mention important details in passing during calls, and email or text about changes as they occur. Your understanding must continually incorporate these fragments while maintaining coherence, which means frequent reconstruction as new pieces arrive.

Importantly, this information matters across multiple legal contexts. A client’s employment situation is simultaneously relevant for income verification, child support calculations, custody schedule feasibility, property division, and potentially attorney fees. Each time you work in one of these areas, you reconstruct not just the employment facts but how they relate to that specific context.

The relationships between facts often matter as much as the facts themselves. For example, when an asset was acquired determines characterization, how income has changed over time affects support calculations, and whether custody preferences align with work schedules determines feasibility.

These relationships exist in your understanding rather than in any single document.

Context often lives primarily in attorney memory. Documents record explicit information such as dates, amounts, events, but they don’t capture the context of conversations, the significance of timing, the reasons behind decisions, or connections between seemingly unrelated events. This contextual understanding matters enormously for strategy but exists primarily outside of the documents.

The Cognitive Load Impact

The mental assembly work creates significant cognitive load that affects practice performance and capacity in multiple ways.

Preparation time expands beyond what should be necessary. What should be a quick file review becomes thirty minutes of reconstruction work. What should be straightforward drafting requires an hour of gathering and verifying information before you can begin writing confidently.

Context switching between cases becomes cognitively expensive. When you shift from one case to another, you’re not simply changing tasks, you’re rebuilding your mental model of a completely different client situation. The startup cost for each case increases substantially as information volume grows, even when that information is well organized.

Decision quality may suffer under time pressure. When you need to respond quickly, you might not have adequate time to fully reconstruct your understanding. This could lead to making decisions with incomplete mental models because building complete understanding would take too long.

The result? Strategic thinking gets crowded out.

The cognitive resources spent on reconstructing “what’s the complete picture” reduce the cognitive resources that remain for “what does this picture mean for our options” and “how should we position this for best outcomes.” The most valuable attorney thinking: strategic analysis and creative problem-solving, requires mental space that reconstruction work consumes.

The risk of missing important connections increases when understanding must be actively reconstructed rather than maintained systematically. You might not remember that the client mentioned possible relocation six months ago when you’re now negotiating custody arrangements where that would be highly relevant.

The Scalability Ceiling

This reconstruction requirement sets a natural limit on the number of cases an attorney can manage effectively, one that exists largely regardless of how well their documents are organized.

With roughly ten active cases, most attorneys can maintain reasonably current mental models. You work on each case regularly enough that understanding doesn’t fully decay between sessions. Reconstruction is incremental rather than complete.

With thirty active cases, maintaining current understanding becomes substantially more difficult. Too much time passes between work sessions. Each time you return to a case, you’re essentially commencing building comprehensive understanding with only basic background. Mental assembly work now consumes a significant portion of working hours.

With fifty active cases, a reality for many family law attorneys, you exist in constant reconstruction mode.

It’s nearly impossible to maintain current understanding across your entire caseload. Relying on your memory alone, every task begins with substantial information assembly before you can proceed to actual legal work.

This ceiling exists regardless of how excellent your document management system is. Better organization helps you find information faster during reconstruction, but it doesn’t eliminate the fundamental need to mentally assemble that information into integrated understanding each time.

The Hidden Time Cost

Consider the time investment using conservative estimates. An attorney managing thirty active family law cases might spend: four hours monthly per case for major preparation events like settlement conferences or court hearings; three shorter sessions of thirty minutes each for motion drafting or settlement evaluation; and four brief reviews of fifteen minutes each for routine matters.

That totals roughly six and a half hours monthly per case spent on information assembly and mental model reconstruction.

Multiply across twenty cases and you reach 130 hours monthly, approximately 33 hours weekly. That’s nearly an entire billable work week devoted to reconstructing understanding that theoretically already exists somewhere in organized files.

This time typically isn’t billed as a separate line item. It gets embedded within other categories or absorbed as non-billable preparation. The opportunity cost is substantial, as that time could be spent on strategic analysis, creative problem-solving, practice development, or building deeper client relationships.

The Information Abundance Paradox

Family law practices today have more information about their cases than ever before. Digital communication means everything gets captured, document collection is comprehensive, and financial disclosure is detailed.

Yet attorneys still don’t have sufficient information at their fingertips when making important decisions.

This is not because relevant information is missing, but because transforming abundant information into actionable understanding suited to specific questions requires substantial cognitive work that must be repeated frequently.

You have the raw information: forty pages of bank statements, months of communications, and extensive asset documentation. However, what you need is your client’s genuine financial position and how it’s changed over time, understanding the real custody dynamics, and how they should be characterized and valued for division. This requires mental assembly work, each time.

This paradox naturally intensifies as information volume increases. More comprehensive documentation should mean better understanding, but it often means more material requiring review and integration during each reconstruction cycle. Better document management helps by making information easier to locate during reconstruction, but it doesn’t fundamentally change the architecture where understanding must be rebuilt rather than persisting systematically.

Client Experience and Commercial Reality

Clients rarely understand the mental assembly work their attorneys perform, but they consistently experience its effects in ways that shape satisfaction and perception of value.

When you need time to review the file before responding to questions, they experience delay. When you ask them to remind you about previously provided information, they may feel unheard. When you seem less prepared than expected in meetings, they lose confidence even when your legal analysis remains sound.

None of this reflects inadequate effort or poor practice. It reflects the reality that maintaining a comprehensive, current understanding of each client’s situation requires time that isn’t always available before each interaction.

Why Further Optimization Has Limits

Better document management certainly helps, with better search capabilities, smarter organization, and more sophisticated classification. These improvements make the reconstruction process more efficient by reducing time required to locate relevant information.

But they don’t eliminate the fundamental issue.

Better search helps you find information faster during reconstruction, but you still need to gather from multiple locations and mentally integrate it. Smarter organization helps you know where to look, but you still need to review across categories and build connections. More intelligent classification helps identify what’s relevant, but you still need to reconstruct how it all fits together.

The primary problem is not access to information. The core challenge is about maintaining integrated understanding that persists across work sessions rather than requiring reconstruction each time.

Document management improvements make reconstruction work more efficient without changing its fundamental nature. At some point, the question shifts from “how can we make this process more efficient” to “do we need a fundamentally different approach.”

Recognizing the Architecture Challenge

The mental reconstruction problem exists because of how information architecture works in most practices: information lives in documents and understanding lives in attorney minds. Documents persist reliably, but understanding must be reconstructed frequently because memory fades and circumstances change.

This architecture made sense historically, because documents were the only reliable medium for storing information long-term, and attorney minds were the only place where integrated understanding could exist. The mental assembly work was unavoidable because no alternative existed.

But technology capabilities have evolved substantially.

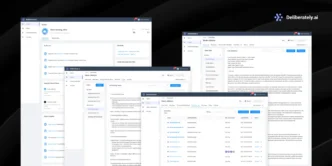

What would practice look like if integrated understanding could persist systematically the way documents do? Not replacing attorney judgment, but preserving the context and connections between facts so that your mental model doesn’t require complete reconstruction each time you return to a case?

What would change if you had access not just to well-organized documents but systematically maintained understanding of that client’s complete situation: the key facts, how they relate, what’s changed since you last worked on the matter, and what questions remain open?

What becomes possible if the substantial time and cognitive energy currently spent on mental assembly work became available instead for strategic analysis, creative problem-solving, or more sustainable work schedules?

These questions point toward reconsidering how family law practice can leverage modern technology, rather than accepting historical constraints from a paper-based world.

What Does This Reveal?

The mental reconstruction problem is real, significant, and essentially universal across family law practices regardless of size or sophistication. Understanding its true cost in time, cognitive load, scalability constraints, and opportunity cost, helps explain why certain inefficiencies persist even in well-run practices and why traditional optimization approaches eventually hit limits.

The question worth considering is whether the substantial investment family law attorneys make in mental reconstruction work represents the best use of scarce resources, or whether different approaches might preserve that capacity for higher-value applications where human judgment, creativity, and strategic thinking genuinely matter most.