Abhivardhan

President & Managing Trustee, Indian Society of Artificial Intelligence and Law

Arunima Jha

Advocate, High Court of Bombay & Patron Member, Indian Society of Artificial Intelligence and Law

On May 9, 2025, the U.S. Copyright Office (USCO) released the third and final part of its series on Artificial Intelligence and Copyright Law, a document that may reveal the cracks in traditional IP frameworks for every IP lawyer, content creator, platform engineer, and policy architect.

The release of the U.S. Copyright Office’s Part III Report on Generative AI and Copyright is significant, as it inadvertently exposes the limitations of AI and traditional Copyright frameworks—particularly in enforcement and practical application. This insight breaks down that report, why copyright may be losing ground, and how alternative legal frameworks are emerging to address real-world economic and competitive concerns across sectors and jurisdictions, with particular focus on India’s proactive stance via the proposed Trade Secrets Bill, 2024, which may signal where regulatory energy is actually heading.

Multi-Market Impact of the USCO Part III Report

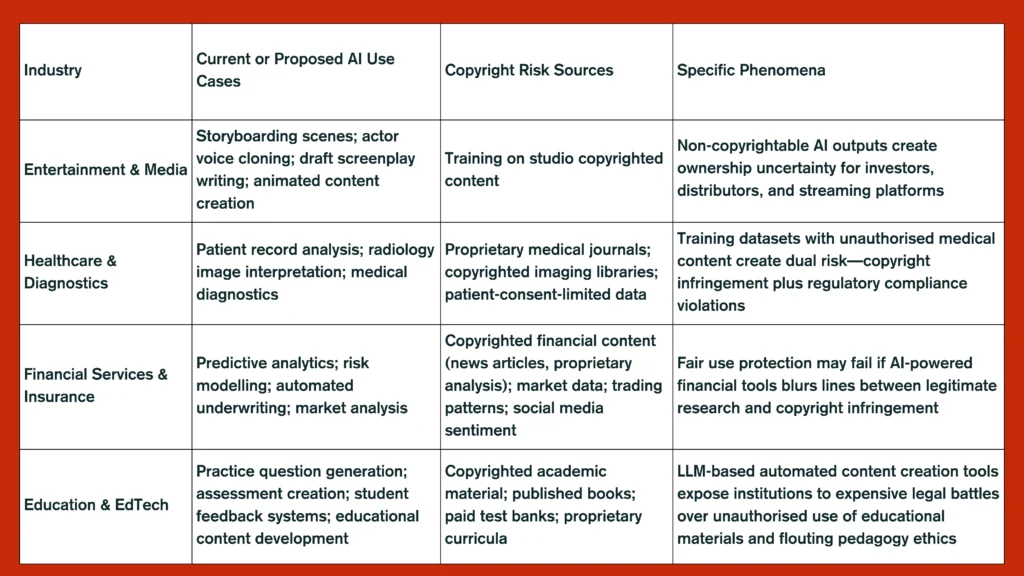

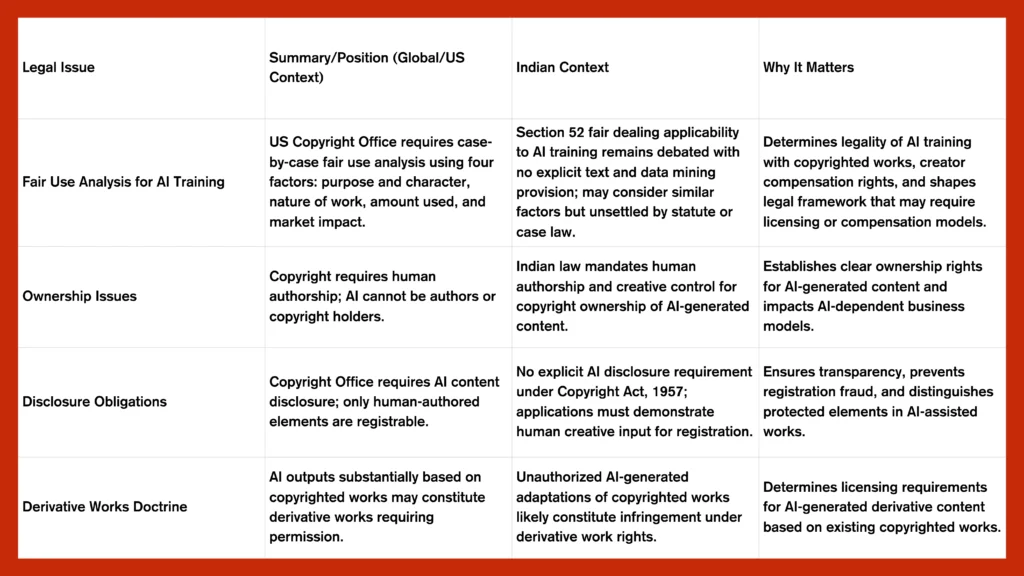

This Part III report addressed whether is it legal to use copyrighted works to train generative AI systems, and whether such use is transformative enough to qualify as fair use. The report stops short of sweeping conclusions, which is [commendable/welcomed], and doubles down on nuance. Every AI training use case, the USCO says, must be examined individually, fact-by-fact, function-by-function, under the established four-factor fair use test. That means courts (and content owners) will be knee-deep in questions (also check Table 2) like:

- What kind of copyrighted material is being used?

- Is the AI system using it for commercial gain or innovation?

- How much of the original work is being consumed?

- And most critically, is the AI model’s use [of the material] harming the market for the original?

Thus, the Part III report may be anchored in law, but its shockwaves are being felt across boardrooms and studios alike. The table below (Table 1) gives a comparative perspective, across five key sectors affected by AI-copyright implications.

Table 1: Comparative Perspective of Economic Law Risks around AI Democratisation as per USCO Part III Report

The Indian Response: Trade Secrets over Fair Use?

Table 2: An India-US Comparative Perspective of AI and Copyright Aspects based on USCO Part III Report

While the U.S. dives into complex fair use calculus to determine what counts as “too much” when training AI models, India might pave a different path, to offer both certainty and strategic advantage to domestic players. The Trade Secrets (Protection and Enforcement) Bill, 2024 proposed under the Law Commission of India, though still in draft form, could a critical shift in how India intends to govern AI’s raw materials (check Table 2): data, algorithms, and proprietary processes.

But before addressing the legal framework, it’s worth examining why copyright reductionism around LLMs fundamentally misunderstands their technical architecture. The prevailing narrative treats AI model weights as somehow “containing” copyrighted works—a conceptual error that conflates pattern extraction with storage. As explained in contemporary inventorship research, deep learning models engage in lossy compression that converts discrete expressive elements into continuous mathematical representations. When an LLM processes text, it doesn’t store retrievable copies but rather updates billions of parameters representing learned statistical relationships between tokens, concepts, and linguistic structures. Modern transformer architectures use embedding spaces where words and phrases become high-dimensional vectors—the distance and relationships between these vectors capture semantic patterns without preserving the specific expressions that generated them. This process is fundamentally irreversible: you cannot reconstruct original training texts from learned embeddings. The so-called “decompression problem,” where AI systems appear to reproduce training data, typically reflects overfitting on frequently repeated content rather than systematic storage—boilerplate language appearing across thousands of training examples makes statistical reproduction more likely, but this represents pattern recognition rather than expressive copying.

Unlike U.S. copyright law, which is built on statutory exceptions and judicial interpretation, India’s move toward codified trade secret protection is about secrecy, not scrutiny. If passed, this Bill will recognise trade secrets as enforceable rights across industries, laying out civil remedies for unauthorised use, misappropriation, or breach of confidentiality. For AI developers, this could be a game-changer.

Why? Because it allows companies to protect how their AI models are trained, without having to disclose that information publicly, as would often be required under copyright or patent regimes. The Trade Secrets Bill’s provisions on “holder of trade secret” rights under Section 3 establish that any information deriving commercial value on account of being secret, and subject to reasonable steps to maintain secrecy, qualifies for protection. This framework is particularly suited to AI model architectures and training methodologies, which the Beijing Intellectual Property Court has already recognized as constituting competitive interests deserving protection even when outputs themselves lack copyright protection. India’s draft legislation defines misappropriation under Section 2(d)(i)(I) to include “acquisition of a trade secret by unauthorized access to, appropriation of, or copying of any documents, objects, materials, substances or electronic files, lawfully under the control of the holder of trade secret, containing the trade secret or from which the trade secret can be deduced.” This definitional language is particularly relevant for AI training pipelines, model weights, and proprietary datasets—the technical substrates that copyright law struggles to categorize, since these elements derive their value not from expressive content but from the competitive advantage of their secrecy and the methods used to develop them.

The Indian approach favors confidentiality, control, and commercial flexibility, especially in a landscape where IP enforcement remains sporadic and cross-border litigation is resource-intensive.

Moreover, Section 4 of the draft Bill explicitly protects “independent discovery or creation” and “reverse engineering” as lawful acquisition methods, while Section 5 carves out exceptions for whistleblowing and public interest disclosures. These provisions create a nuanced framework that acknowledges the technical reality of AI development: that pattern learning from publicly available data differs fundamentally from misappropriation of proprietary training methodologies. The Bill’s approach to defining trade secrets through qualifying criteria—secrecy, commercial value, and reasonable protective steps—rather than categorical definitions, provides the flexibility needed for AI innovations that blur traditional IP boundaries. Crucially, Section 6 incorporates compulsory licensing provisions for circumstances of “national emergency or extreme urgency involving substantial public interest, including situations of public health emergency, national security,” ensuring that trade secret protection doesn’t become a mechanism for indefinite monopolization of critical AI capabilities.

This also positions India differently on the global stage. While the U.S. struggles to balance creative rights and innovation, Indian law is leaning into a “don’t ask, don’t tell” model, one that rewards those who control the data pipelines and build training corpuses from scratch or open-access sources.

But this isn’t just about policy. It’s about economic alignment.

Indian tech companies are emerging as major exporters of AI services and there is growing government interest in sovereign data governance and indigenous LLM development, evidenced by the IndiaAI initiative backed by ₹10,000 crore and plans to provide access to over 10,000 GPUs for training and research.

Yet, there is still no legislative appetite (or that there exists a probable “regulatory overhang”) for expansive fair use doctrines, especially when global platforms are involved.

The result is a legal environment where training data can be kept under wraps, LLM outputs can be commercialised swiftly, and disputes can be contained within confidentiality frameworks.

However, this also raises critical questions:

- What happens when Indian AI models are exported to jurisdictions that follow the U.S. copyright approach?

- How will courts reconcile trade secret protections with copyright infringements alleged abroad?

- And what about transparency requirements for bias audits or ethical AI benchmarks that demand visibility into training datasets?

India’s upcoming legislation may solve one set of problems, but it could just as easily create new cross-border compliance challenges.

Conclusion

The U.S. Copyright Office’s Part III report confirms that training inputs matter, fair use isn’t automatic, and human authorship remains central to copyright protection. But it also exposes a deeper truth: copyright frameworks weren’t built for AI’s pattern-learning architecture, creating enforcement gaps that trade secret law may be better positioned to address.

For legal teams, this shift demands new questions:

- Have our AI vendors trained models on third-party copyrighted material without adequate licensing?

- Do our contracts reflect the IP and indemnity risks tied to generative AI across multiple jurisdictions?

- Are we equipped to maintain the “reasonable steps” standard for trade secret protection once India’s Bill passes?

- Do we have cross-border playbooks for exporting AI systems to markets with divergent IP frameworks?

The AI revolution doesn’t just need engineers—it needs lawyers who understand copyright, contracts, confidentiality, and competition law simultaneously. In the world of generative AI, it’s not just about what the machine creates. It’s about what you let it learn, and whether you can prove you had the right to teach it.